Back in 1999, a young Justin Butterworth had an inkling the internet might be a big deal. Over the next 12 years, he launched, scaled and eventually sold his first property-tech startup, Rentahome.com.au — a short-term letting startup cited as a success story in Airbnb’s first pitch deck.

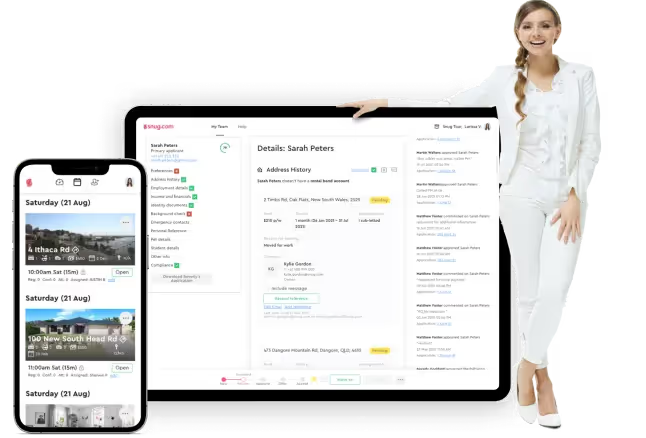

Today, Justin is founder and CEO of Snug, a real estate platform designed to improve and streamline the application process for rental properties.

Snug is growing in terms of users, revenue and employee-count. That growth, at least in part, has been fuelled by debt funding from Tractor.

And the revenue generated by the Snug platform is being invested into a secondary, more experimental offering — something that’s breaking new ground in the property sector.

Snug’s funding story

With Snug, Justin has always had “a frugal mindset”. Initially, he self-funded and bootstrapped, keeping costs low while he defined the customer problem and fine-tuned the solution.

To seed the business, Justin personally invested $1m and raised $630,000 from angel investors, “who were strategically aligned and brought experience, connections and expertise contribution”, Justin says.

Since then, Justin has taken two rounds of Tractor funding.

Snug’s platform is used by some 3,000 real estate agents, and is integrated with 60 partners, ranging from the likes of Domain to identity service providers to financial services firms.

With 15 employees on the books, Snug has supported more than 1.5 million renters, Justin says.

Still, the founder currently retains 80% of the business.

“We’ve always been able to reduce the overhead of capital raising, and reduce or remove the dilutionary impact,” he says.

Putting Tractor to work

Primarily, Justin and the Snug team have used Tractor funding to invest in sales and marketing teams and activities — that is, clear levers for revenue growth.

In fact, the return on investment (ROI) per salesperson has been anywhere from 500% to 900%, Justin says.

At the same time, the SaaS product allows for speedy repayment.

“Compressing the SaaS revenue cycle to under 30 days — from demo to ‘deal-done and cash-in-bank’ — means our ROI from venture debt funding is quick, as well as high.”

But Snug is not purely a SaaS startup. That’s where the debt funding proposition becomes a little more unusual.

Most of Snug’s surplus revenue is directed towards the development of what Justin calls “a speculative second-platform product”.

This is an alternative to ‘traditional’ home ownership; a fintech product opening up property investment opportunities through a diversified real estate investment trust.

It’s an innovative and experimental product, with much longer revenue lifecycles, and significant costs associated with licensing and R&D. It’s the kind of product that would usually be fuelled by equity funding.

But in Snug’s case, the need for venture capital is negated by the revenue the core platform is generating; revenue that is trending upwards, not least because of investments made using debt funding.

Angel vs VC vs debt

Justin has taken equity funding in the past and will consider doing so again. For him, there’s no right or wrong path for any business. It’s all about the type of business, the market it’s operating in, and the goals the founders hope to achieve.

“The motivation of the capital should be aligned with the trajectory of the business,” he says.

Businesses launching one specific product into a wide market may be well-suited to VC — particularly if they’re low-barrier-to-entry, with a high possibility of competitors emerging.

Here, “speed to market is paramount for survival and success,” Justin explains.

“You need a barrelful of VC gunpowder.”

But, Snug is almost the polar opposite to this. It’s a complex, multifaceted product, solving problems throughout the housing ecosystem. There is little competition, but high barriers to entry.

“We had to take a more measured approach to understanding the customer problem, product ideation, MVP and go-to-market,” Justin explains.

With that said, he also notes that raising VC capital can be incredibly time-consuming, and a distraction for founders who could otherwise be focusing on building their business.

As a founder with some experience and success under his belt, Justin advises founders to learn more about venture debt and other routes to capital, rather than rushing into VC because they feel that’s what startups ‘should’ do.

“Is the capital aligned with your organisational objectives? And what is the true cost of capital, in terms of management distraction?”

Sometimes VC is the perfect solution for a startup. But a mismatch has the potential to be catastrophic, Justin warns.

“Distraction, dilution and disaster. They're the three Ds of capital raising,” he says.

“It will take up your time and dilute your equity. And the ‘disaster’ is that you may be forced to hand over the business if VC outcomes are not realised.”