According to the oracle that is Investopedia, impact investment in the US dates back to the 18th century, when methodists protested the slave trade, smuggling, liquor, and gambling by diverting their cash away from those assets.

Even religious laws allude to ethical investments dating back to 1,500 BC.

So while today, ‘impact’ is a buzzword in startup circles, with investment in the space on the up and up, it’s not necessarily anything new. In fact, as fallible humans, it’s arguably in our nature to support those who share our values, to follow our best instincts, and to back – financially or otherwise – people bringing good things to our communities.

Impact businesses are simply those creating positive change in the world in one way or another. That could be focused on the environment and tackling climate change or social impact, championing equality and improved human experience.

Often they’re working towards one of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals – things like ending poverty, promoting health and well-being for all, clean energy, or more inclusive societies.

They’re not charities or NGOs – being lumped into that category can be a barrier to growth.

They’re companies making money and achieving profitability. They provide services people want and need and appeal to an increasingly conscientious customer base.

In startup land, they also operate in deep tech and hardware, cash-intensive industries requiring significant runway.

How is the space growing?

In its 2023 Impact Startup Benchmark Report, Australia’s first impact-focused venture fund Giant Leap reported that about 22% of Aussie startup funding in 2022 could be classified as ‘impact’ businesses. That’s up from just 15% in 2015.

High-profile entrepreneurs like Atlassian founders Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar are now playing in this space loudly, and there is a growing awareness that consumers are driven by their values.

According to dealroom.co, impact startups raised a combined US$68 billion in 2021, more than double the $31 billion raised in 2020 and up more than 2,000% from the meagre $3 billion invested in 2011, ten years previous.

2021 was an outlier year, and at the time of publication, the report predicted a dip in impact investment for 2022 to US$47 billion. Still, the upward trajectory is undeniable.

Social impact and sustainability are no longer confined to the fringes, and founders in these spaces are no longer met with rolled eyes and condescending smiles.

Part One: Explaining Impact

Impact startups span various sectors, markets, technologies, and ambitions. As cliche as it may sound, the one thing they have in common is a general – yet genuine – desire for their business to leave the world a better place.

Giant Leap defines impact startups as: “Rapidly scalable businesses that blend financial returns with real and measurable social and environmental benefits.”

Elsewhere, Entrepreneur.com coins the hideous phrase ‘impact-preneurs,’ saying these are people “committed to solving a large-scale social or environmental problem.”

We also put the question to ChatGPT (because how could we not?). The AI defined impact business as: “a type of company that aims to make a positive impact on society and the environment while also generating profits.”

It then got a little self-contradictory and added NFPs into the mix, but hey, it was halfway there.

Whatever your definition, when it comes to actually running a business, the notion of ‘impact’ is a little more nuanced.

In Tractor’s portfolio companies, impact shows up often and in various ways.

CarbonCrop operates in the environmental impact space, using AI to help landowners get paid for restoring and maintaining forests.

But not every story is quite as clear-cut, and even where impact appears, it’s not always immediately recognised… even by those creating it.

Bluebell

Bluebell is a startup operating in the mental health space, making new and alternative science-based treatments more accessible to patients.

It offers pathways to mental health services through its boutique clinics and partnerships with doctors, with treatments including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a relatively new treatment that has proven effective for patients who haven't responded to a range of antidepressants. TMS has been studied for about two decades and has been TGA/FDA-approved since ~05 - ~07, included on the Australian depression guidelines since 2015.

Founder Josh Mikel has worked in various healthcare settings, always focusing on providing the best patient experience possible. However, before our interview, he had never considered himself an 'impact' entrepreneur.

"I really like healthcare because if you're with the right people and you're building a network that has a good patient experience, and those patients get well as a result of what you're doing, it makes it very easy to come to work every day," Josh says.

This is Josh's first startup, and that drive for better patient experiences has shaped how he runs things.

"I've been able to tell my staff that our priorities are excellent patient experience and gold-standard clinical care. We push anything that gets in the way of that to the side."

HEX

Jeanette Cheah heads up HEX, a Melbourne-based edtech which (as she puts it) is "bringing universities kicking and screaming into the future."

She explains that impact from an environmental and sustainable sense is straightforward. Social impact through education can be trickier.

HEX provides innovation, entrepreneurship, and futurist education through various out-of-classroom immersive experiences.

Jeanette talks about building 'exponential intelligence,' meaning the skill sets, mindsets, and toolsets young people need to succeed. That includes community, ethics, and critical thinking – it's helping future leaders to lead with empathy, and that can only be a net positive.

But in the early days, she didn't identify HEX as an impact business.

"Even though I would sit in a room and watch impact being created in those students, I wouldn't have gone out to the market and self-identified as an impact business," Jeanette explains. "It's interesting to see that other people from the outside can see that we have a positive impact and would label us like that."

"I believe education is a crucial component of training the future workforce and leaders. But it's also a great opportunity to impart new values, new ways of thinking, and empathy to the people you teach."

"We teach this 'gap year segment' – upper secondary through to university – because that's where they're learning how to treat each other. They're learning how to think about the world and their place in it."

"If we can have an impact at that time and educate them in futurist mindsets, their relationships, their community and their obligations to it, and the ethics of technology, then I believe we're impacting the future workforce and future leaders."

Glow

Glow is a market research company making it easier to gather insights from any given audience quickly to support brands’ decision-making.

On the face of it, this isn’t the kind of impact we’re talking about. However, founder Tim Clover has always been firmly convinced that businesses should do good where possible. So while Glow’s business model doesn’t have impact at its core, the company itself does.

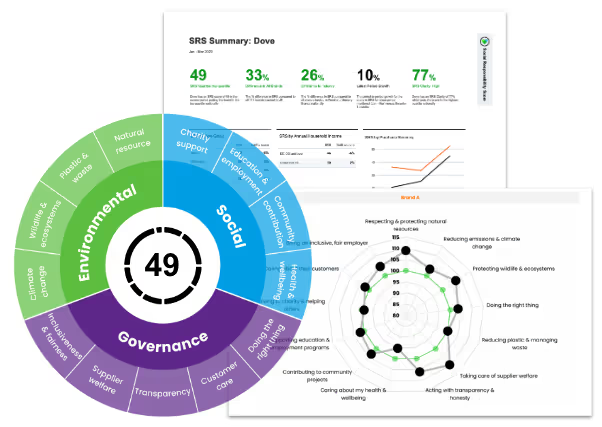

Data, Tim says, can be used to motivate others to do better.

In 2022, Glow released its Consumer Sentiment Food and Drink Sustainability Report, which measured public perceptions of whether a business is socially responsible.

The idea was to use Glow’s data to show companies how much social responsibility means to their customers and to warn them that “if they don’t move with what people want, they’re going to be soon irrelevant.”

“That, for us, was a considered, innovative way of using our platform to make more of an impact with a commercial data product,” Tim says.

The fact that this is a commercial product is essential for the founder. There’s a business to run. If no funds were coming in, Glow wouldn’t be able to produce this kind of content and make this kind of impact.

“It has to pay for itself, and it’s something we feel is a 100x opportunity for us to make an impact.”

Glow has internal projects, too, measuring the carbon footprint of its servers and data centers, for example. But this is where Tim believes this type of business can truly drive change.

“In terms of looking at how we can magnify the impact we make, we think that good data in the hands of important decision makers are probably the most impact we can make.”

Tim is yet another founder who doesn’t identify strongly with the ‘impact’ label. But he is “hell-bent on making an impact.”

gathera

Co-founders Dilhan Wickremanayake and Peter Cole describe their startup gathera (formerly known as Urban Plant Growers) as an urban agtech company. It's a vertical farming solution using Hydroponics and LED lighting to bring veggie patches indoors, reducing food miles and the carbon footprint of your salads.

The team also sets up its systems in offices, cafes, and restaurants, helping 'greenify' public spaces and allowing businesses to grow food at the point of consumption.

For Dilhan, part of what makes a social enterprise is how essential the ethical or sustainability piece is to the business. If you took that part out, he asks, would the business still exist?

For gathera, the answer is 'yes.'

"But it's a complicated one because what drives us is sustainability," Dilhan says. "Making our products as sustainable as possible and then using that as a conduit to incentivise better environmental action is where we can play a positive role in society."

The impact here also goes beyond the environment. For some customers, gathera's tech offers food security in the face of extreme weather events. Others have cited the mental health benefits of having green space in apartment buildings, particularly during COVID-19 lockdowns.

One elderly customer has been able to continue gardening – which keeps her grounded and connected to nature – even after kneeling outside became too strenuous.

Most customers talk about how important sustainability is to them, Dilhan explains. But there's an element of social impact here that the founders didn't necessarily see coming.

Financing hardware for good

Businesses like gathera are striving to affect change in incredibly capital-intensive spaces. Shockingly, vertical farming systems and autonomous aircraft are costly to build, yet revenues depend on the existing physical product.

Tractor Ventures financing is designed to “align repayments with the heartbeat of the founders’ business,” Tractor Co-Founder Matt Allen explains.,

“We see an opportunity for hardware companies focussed on social impact to access a new type of funding – the ability to build, test, and certify products before delivering them.”

“The Tractor team takes the time to understand the mechanics of the business and the cash flow operations – the product lifecycle, the componentry and inventory, and the supply chain issues reliant on capital to problem-solve for.”

Tractor’s new Inventory Advance funding model takes this further, opening up more opportunities for hardware tech.

Co-founder Aprill Enright-Allen explains: “Originally, we’d funded gathera and other companies with an alternative type of alternative funding, which evolved past our first funding method of revenue-based financing and towards an inventory advance model.

“The longer-term hope for Tractor Ventures is that we change the nature of business lending by solving founders’ common financial problems, which traditional banking institutions can’t solve for.

“We’re looking to bring the humanity back into finance.”

CarbonCrop: Making reforestation profitable

Fitting neatly into the sustainability impact mandate is Kiwi startup CarbonCrop.

As CEO Jo Blundell puts it, CarbonCrop “points some satellites at some trees” and uses a machine learning model to measure the carbon stock and ongoing sequestration of forest areas. Using this data, CarbonCrop helps landowners to participate in New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).

In theory, anyone can register forest on their land with the ETS and receive New Zealand Units (NZUs), a type of carbon credit, which can be sold to companies to offset their emissions.

However, forests must meet a particular set of criteria to qualify, and an assessment can cost thousands of dollars.

“The scheme just was not accessible for average farmers,” Blundell says – or frankly for anyone with acreage at their disposal.

CarbonCrop's tech can identify what kind of forest landowners are dealing with, whether it qualifies, and what they could potentially earn for it. The startup then manages customers’ participation in the ETS, monitoring land and ensuring continued compliance.

All of this means more long-term protection of forests and biodiversity, with financial incentives to boot.

CarbonCrop's sweet spot has been assessing native, biodiverse forests at scale. Previously, of about 300,000 hectares protected under the ETS, about 40,000 hectares was a native forest.

Over the past 12 months alone, CarbonCrop has added another 10,000 hectares of indigenous biodiversity – boosting coverage by 25%.

Having signed its first customer in July 2021, the startup is now distributing the first units earned by customers, with payments totalling some NZD $20 million. About 80% of that is funding for a native forest.

The problem CarbonCrop is solving is more than just a New Zealand one. There are schemes similar to the ETS worldwide and a global market for voluntary carbon offsets.

“As we continue to grow and learn and figure out who we are and what we are, we’re looking to the global market,” Jo says. “I see no end to the opportunity to improve how we look after nature and use technology to monitor and measure the success of that."

Part Two: Changing Attitudes

Giant Leap launched its first impact fund back in 2016. At that time, partner Adam Milgrom says most people had never heard the term' impact investment'.

Adam (who has also made a personal angel investment into Tractor Ventures) was having conversations about whether it was even possible to build a great business and make a significant impact at the same time.

"The vast majority of that conversation isn't there anymore," he says.

Now, plenty of examples point to where businesses are making money and impact simultaneously – and VCs are taking notice.

Some of the biggest Aussie investment firms have added 'head of impact' roles in the past few years.

And while it's not necessarily getting easier for impact startups to secure funding (if anything, Adam says, obtaining funding is getting harder for everyone), they're being noticed and discounted in how they might have been just three or four years ago.

"We were lumped in a bucket of philanthropy," Adam explains. "I don't think that's happening anymore. We're now looked at as a legitimate area of financial investment."

CarbonCrop CEO Jo Blundell has seen this shift at a personal level. Before joining CarbonCrop, she had a storied career in New Zealand's tech ecosystem, holding senior positions at the likes of Xero and Timely.

But ten years ago, in the early days of the online shopping revolution, she founded an online store selling ethically-made products.

"I saw this fast-fashion, consumption craziness … and I got really disturbed and upset," she says.

Jo wanted to offer a place for people to shop more conscientiously, with transparency as to what they were buying, where it came from, and how it aligned with their values.

It didn't take off. This problem kept Jo up at night, but she realised she was the exception, not the rule.

"I really thought about it. I felt anxious about how everyday people lived and how I lived. But that didn't extend to your average consumer," she explains.

"I think that that's changed, and it's changed at all levels, across all businesses, and all industries. Everybody is thinking about it and talking about it."

"Not long ago, any mention of ESG or sustainability was met with a sigh and an eye roll. Companies are now trying to measure and reduce their carbon footprints and create more sustainable businesses."

Supply and demand

One of the critical findings of Glow’s Consumer Benchmark Report was that, in the food and grocery industry, at least 89% of Australian consumers expect brands to behave responsibly.

Some 60% of consumers said a company’s purpose and values play an essential role in their purchasing decisions, and 25% said they had put their money where their mouth is, changing brands based on their perception of ESG performance.

This trend is particularly prominent among millennials and Gen Z consumers. A 2020 report from First Insight found that 62% of Gen Z and Millennial shoppers prefer to buy from sustainable brands, compared to 54% of Gen X and 39% of baby boomers.

Gen Z and Millennials are also likely to purchase based on personal values and social and environmental principles.

These are young professionals with a ridiculous amount of spending power. And they’re not likely to shift from this trend anytime soon.

The Glow report also analysed about $1.3 trillion worth of sales data from consumers in the US, measuring how much brands have grown compared to how socially responsible people perceived those brands to be.

Unsurprisingly, there’s a correlation. Over three years, the brands perceived to be more responsible have grown more.

Glow’s research suggests we’re getting to a point where evidence is quantifiable, and for Tim Clover, that’s part of how he wants Glow to move the needle.

“We hope sustainability leaders will have more data to argue their case in the boardroom, which means the ultimate impact – whether that’s second or third order in the effect of our work – is that it’s helping to turn the ship.” - Tim Clover, Glow

But ‘perception’ is a key word here – any links between consumer spending and ethical enterprise can be somewhat muddied by skepticism around false claims and things like greenwashing.

Equally, while several reports have surveyed consumers and found them willing to spend on ethical products, that doesn’t always equate to them doing so.

According to Giant Leap’s Adam Milgrom, there will always be consumer resistance to trying new things, paying more money, or compromising on the quality in the name of social responsibility.

Customers would like to be more purpose-driven, but when it comes down to it (particularly during a cost-of-living crisis), sometimes the barriers need to be lowered.

It’s worth noting that when asked why they spend with sustainable brands, respondents to the First Insight report ranked ‘quality’ more highly than ethics or environmental concern. That was true across all generations.

So Giant Leap focuses on areas where the beneficiary is the customer. Both Giant Leap and Tractor Ventures have backed HEX, for example, a startup that exists to serve primarily those it is educating.

“Historically, education, healthcare, and energy companies didn’t think with a consumer mindset,” Adam says.

“They were serving different stakeholders. Those stakeholders are increasingly coming at it from a consumer mindset, where they’re driving value for the consumer and ensuring the consumer is the ultimate beneficiary.”

A note on B Corps

Ethically-run businesses can apply for B Corp certification, showing they meet high standards across employee benefits, charitable giving, and supply chains.

Becoming a B Corp can build trust with customers and communities and help businesses attract and retain employees. They must repeat the verification process every three years, so they must be focused on continuously improving their practices from an ethical standpoint.

For Adam Milgrom, there are two ways to consider a company’s impact.

The first is what the business does: what it sells to make its revenue.

The second is how the business is run:

- How staff are treated.

- How the team works with stakeholders.

- How it interacts with its environment.

This is where B Corp certification comes into play.

While it can be a boon in the B2B sphere, he says B Corp certification could be better known in the consumer space. And either way, it requires significant trading history and processes embedded enough to be analysed.

At the early growth stages of a business, that’s often not possible.

When making investment decisions, Giant Leap looks at both the ‘what’ and the ‘how,’ Adam explains, but in a more simplified way, that’s more relevant to a startup.

“We don’t want to be working with companies that are virtuous with the ‘what’ but doing it in a way that’s negative to their community.”

Tech evolution

Where consumer demand drives supply, in hardware businesses, supply is also driving demand. gathera's business model is a perfect example of this.

The agtech space is booming, and food security is high on the agenda. But gathera operates in a niche within a niche. It’s producing hardware, but it’s not quite industrial, and it spans the B2C and B2B markets.

Co-founder Peter Cole notes that a business like this couldn’t have existed ten years ago – the LED light technology that powers the vertical farming tech has come on leaps and bounds over the past decade.

“The technology has caught up with market demand.”

Ultimately, Peter sees a future of beautiful and completely modular products, creating ecosystems that grow with the customer’s needs. That could be a complete fit-out on the wall of an inner-city apartment or an indoor garden at a cafe or restaurant.

It’s a future where the leaves for your lunchtime salad are picked right before you, where that food has zero carbon food miles, and where supply is secure.

For co-founder Dilhan Wickremanayake, the big, audacious goal is focused on the quality of that product. Genuine sustainability means reducing carbon emissions in the long term – including in manufacturing – and building something that will last, he says.

Part Three: Cause for criticism?

Finally, companies striving to be better in terms of environmental or social impact may find themselves facing up to hypocrisies.

Should a business focused on mental health also use renewable energy and offer exemplary employee experience while championing charitable causes?

For a scrappy startup just trying to make ends meet, that’s arguably impossible and might come at a detriment to profitability – even survival.

Yet, if you claim to be making positive changes in one area, you risk being called out for failing in another.

For Adam Milgrom, this is another iteration of ‘tall-poppy syndrome,’ the phenomenon whereby those who are successful find themselves publicly cut down to size. It’s a broader societal issue, and while it’s not something he sees portfolio companies worrying about too much, he would like to see that narrative change.

"I think it's a pity that we let arseholes be arseholes, and we hold people trying to be good up to such a standard that they can never be good enough. We criticise someone who espouses their intention to be good but has never been good enough while at the same time letting people who don't care about being good at all get away with doing things that are damaging" Adam explains.

"There is more pressure for companies trying to do good to meet a higher bar than companies that aren't trying. You have to be reasonable as a company about what bar is appropriate, but there are considerable benefits to meeting that bar – and it does set you apart, providing you don't do it to the detriment of the underlying business."

Adam further elaborates that the Giant Leap approach is "continuous improvement and not letting perfect get in the way of better because that's the only way to progress. You can't wait for perfect; it's a false idol."

Regarding the fight against climate change in particular, CarbonCrop CEO Jo Blundell suggests that the fear of being called out for greenwashing is slowing progress. Many businesses would instead do nothing than risk getting it wrong and facing the backlash.

Instead of accusations, she's calling for more curiosity and conversation. Of course, there are bad actors, but she believes most businesses are doing the best with what they know.

"Nothing we do is perfect. That's just a reality," Jo says.

"There is no perfect response to climate change, and we'll make many mistakes. But we're actually out of time. We need to start taking action; it can't be nibbling around the edges. It needs to be quite drastic and a rapid response."

"The only way we can do that is by putting ourselves out there and taking risks."

Part Four: Who Will Win? (And who’s already winning?)

Through these case studies, it’s apparent that businesses don’t need to change the world to make an impact single-handedly.

No company can correct every wrong in the world – and no one is claiming to. But small steps start to move the needle, and enough small steps can lead to significant change.

The sheer number of impact-focused businesses in Tractor’s portfolio shows that many business models are working. By definition, these businesses are generating revenue and taking on funding to kickstart their next phase of slow and steady – yet authentic – growth.

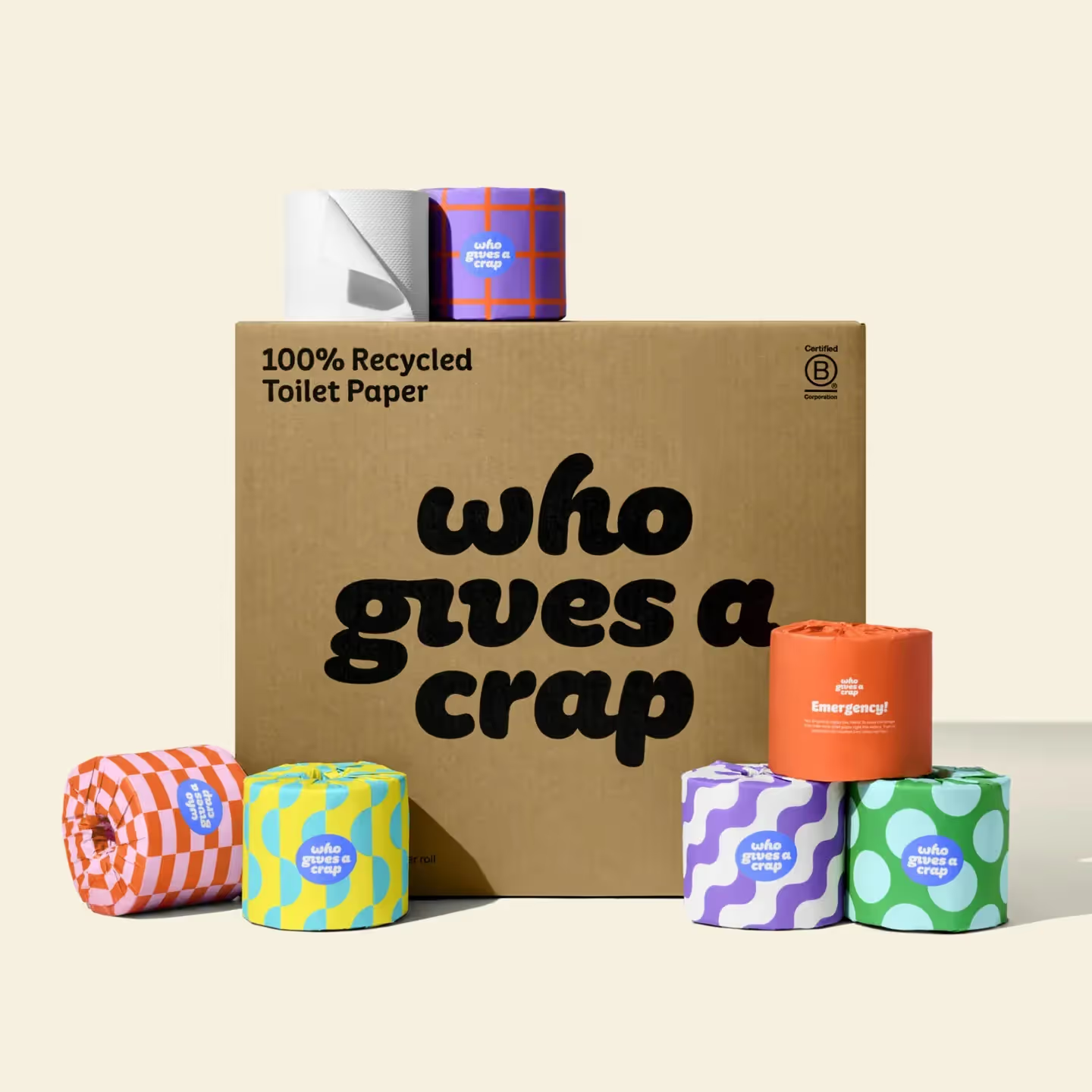

Case study: Who Gives a Crap

Toilet paper subscription startup Who Gives a Crap is one of Australia's most successful social enterprises. Its bamboo rolls in colourful wrapping add instant street cred to many a bathroom across Aussie businesses and households. It's plastic-free packaging now lands on doorsteps across the US, the UK, Europe, and Canada.

WGAC was founded partly to tackle a sanitation crisis in the developing world. Since its inception in 2012, 50% of profits have been donated to projects building toilets and sanitation systems where they're most needed.

The startup has donated more than $11.2 million to clean water projects, meaning its subscription model for planet-friendly TP and clearly defined profit-for-purpose angle has generated total profits of more than $22.4 million. It's also now a certified B Corp.

In 2021, after bootstrapping for nine years, it closed a $41.5 million funding round – a watershed moment for a business that gives away half of its profits.

Part Five: What happens next?

Winning businesses can maintain a robust business model and continue to delight their customers – and increasingly, that delight comes via impact and value alignment.

However, the businesses that really have the edge will be those that can attract the best talent. Here, again, impact businesses have the advantage.

While there are still barriers for consumers, Adam Milgrom says there’s a clear trend of employees hoping to work with impact businesses.

“We have a huge influx of people coming to us looking for positions within the companies we work with because they want to be able to progress their career still and still earn an appropriate salary but do it working with a company that they believe in,” he explains.

“There’s a big opportunity there because those people tend to work much harder and are more productive where they align to the values.”

It’s a competitive advantage, he adds, and that’s something investors are paying attention to.

Jeanette Cheah considers the opportunity from an employer branding perspective: "How you describe your business, values, and goals influences the type of candidates you attract."

There’s not necessarily a right or wrong answer, but if you’re not deliberate in how you brand yourself as an employer, you’ll do it accidentally.

In Jeanette’s experience, Gen Z employees, in particular, want to work on things they’re passionate about. They want to feel proud when they talk about what they do.

“There’s a generational shift around what makes a good career, what’s a good job, and what’s a good boss.”

Jeanette hopes that HEX can empower young people to take their values into their work, giving them the skills to communicate and live up to them. Even if they’re not working at impact-focused companies, young people can build impact into their roles and create change from within.

“If we can create this groundswell of the new workforce, they’re going to be a force from the inside to lead a company to change.”

Scrapping the segment

Adam hopes every investor will one day be an impact investor, and Jo hopes that every business will be sustainable. Many of the impact-focused entrepreneurs we spoke to for this article had no desire to be an anomaly; they wanted others to follow suit.

“There won’t be this impact segment of the market,” Jo says.

“It will just be table stakes that your business is a responsible citizen. That’s what it needs to be.”

According to Tim Clover (and Glow’s data), 9% and 12% of people actively seek brands that align with their values. Once that hits a tipping point of 15% to 20%, that will start trending up fast.

When that happens, businesses that aren’t on board will have “an existential problem,” Tim says.

He adds that those who lead the pack will ultimately do better than the late followers.

“Being dragged kicking and screaming to do the least you can to try to pretend you care about something is not going to wash well with an ever-informed consumer who has got good information at their fingertips instantly now,” Tim says.

“There’s nowhere to hide.”